Local History Features

Contents

1. Waterway 15 and the Restored Boat Bench

2. Freeway Hall

3. A Catamaran Built in Wallingford

4. The Wallingford Steps

5. Lunde & Stoe Residences – Meridian Ave N

6. Wallingford’s Waterfront Quonset

7. Twin Craftsman Bungalows

8. The History of Wallingford Playfield

9. The Rubber Tree: Wallingford’s One-of-a-Kind Contraceptives Shop

10. Public Art in Wallingford: Animal Storm

11. Unemployed Citizens League

12. Wallingford Victory Garden – Corliss & 38th

13. The Genealogy of a Wallingford House

14. Re-discovered Photo Shows Early Wallingford Business

15. 1939 & 1952 Cookbooks by Wallingford Women

16. Relocated Bassett House has Colorful History

17. Street Renaming in Wallingford, Fremont, & U District

18. Willis & Alice Batcheller House – 1848 N 51st Street

19. Swanson’s Shoe Repair: A Fixture of Wallingford

20. Wallingford and Jud Yoho’s Bungalow Magazine

21. Interlake Public School & Wallingford Center

Waterway 15 and the Restored Boat Bench

Posted October 10, 2025

This story was featured in our 2024 Exploring Wallingford activity.

Lake Union has long played a pivotal role in Seattle’s industry, tourism, and recreation, and for thousands of years before that, for Indigenous cultures. Among the lake’s major modern transformations was the opening of the Ship Canal in 1917 (including the Fremont and Montlake Cuts and Hiram M. Chittenden Locks in Ballard). With this came an increase in maritime traffic and industry on Lake Union and as a result, 23 waterways were opened around the perimeter of the lake, eight of them on the north shore in Wallingford (Waterways 15-22) that have been featured in guided walking tours in recent years. These waterways served as entry/exit points for transport of goods and people by boat. Today, these state-owned waterways are managed by the Washington Department of Natural Resources; of the 23 established, 18 remain open.

One of the most distinctive is Waterway 15 located directly west of Ivar’s Salmon House in Wallingford. The waterway was developed in 1993 into the park we see today as mitigation for a storm water project. It includes tables and benches, a curving path with decorative paving, a shallow beach, and of course downtown views. The space also includes public art and historical interpretation in the form of names and terms speaking to the historical development of the lake stamped into some of the paver bricks; a hatch cover with a relief map of the Lake Union area and a short story of the historical location once known as Latona; and 62 silk-screened tiles mounted to boulders with historical photographs of the neighborhood and the lake’s industrial and Indigenous history. In one area of the park, the bricks and images pay homage to the first people to live by the lake, for whom “this water was life-giving.” This tribute includes some bricks with words stamped in the native language.

The park and public art at Waterway 15 reflect the work of artists Elizabeth Conner and Laura Brodax, landscape architect Cliff Willwerth, Judith Caldwell, David Gulassa and Co., and Dick Wagner and the Center for Wooden Boats, which provided a custom-designed, curved bench. Approximately 16 feet long, the “boat bench” was removed to the Center for Wooden Boats’ facility in the fall of 2023 for restoration and reinstalled in 2025.

The park was recognized in 1993 with an Honor Award for Design by the American Society of Landscape Architects, WA Chapter, and again in 2000 with a Cultural Achievement Award by the American Society of Interior Designers, WA Chapter.

Sources:

“Center for Wooden Boats Restores a Treasure on Lake Union,” 4Culture

“Walking Wallingford’s Waterways,” Wallyhood Blog

Thomas Veith. A Preliminary Sketch of Wallingford’s History, 1855-1985. 2005 .

Freeway Hall

Posted September 6, 2025

This story was featured in our 2024 Exploring Wallingford activity.

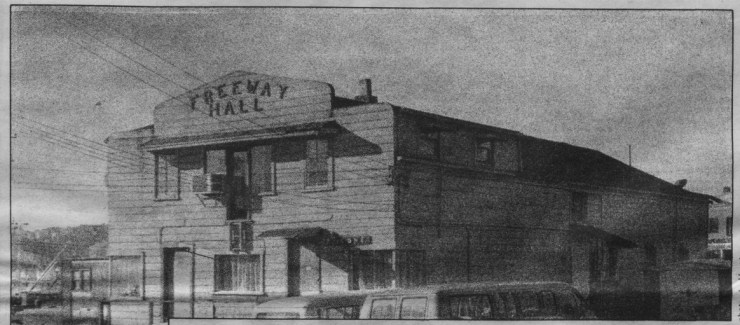

This former warehouse was at the center of Seattle’s progressive political movement from 1963 to 1985. Freeway Hall, 3815 5th Avenue NE, was the world headquarters of the Freedom Socialist Party and Radical Women, a feminist socialist organization, and was a gathering place for other political groups.

The building, named in the 1960s for its location near Interstate 5, reflects the area’s changing uses in the former industrial area of lakeside Wallingford. Built in 1940, it functioned as Kincaid’s Cabinet Shop by the late 1950s. In 1963, the local branch of the Socialist Workers Party moved into the building, and within a few years it was home to the Freedom Socialist Party (FSP) and the Radical Women.

During the 1960s and 1970s, it was a base for the anti-war movement, women’s liberation, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the civil rights struggle, community organizing on behalf of the gay and lesbian community and Chicano/a and Native rights, labor defense work, and more.

Ivar Haglund purchased the property in 1978 with plans to demolish the building to make way for additional parking for his famed Salmon House across the street. He gave the FSP and Radical Women notice to vacate by January 31, 1979. The ensuing uproar not only bought more time for the tenants, it apparently saved the building. Radical Women co-founder Gloria Martin said at the time, “The proud saga of Freeway Hall entitles it to be declared an historic monument.” (The property is not officially designated at the local, state, or federal level.)

Today, the building is home to JAS Design Build.

Sources:

The Freedom Socialist (Summer 1976), p. 16.

Gloria Martin. “Freeway Hall.” The Freedom Socialist (Spring 1979), p. 9.

Gloria Martin. Socialist Feminism: The First Decade 1966-76 (2nd ed.). Seattle: Freedom Socialist Publications, 1986.

Radical Women.

Seattle Gay News, Feb. 2, 1979, p. 5.

Barbara Winslow. “Seattle Radical Women,” History Link essay 2152.

Thomas Veith. A Preliminary Sketch of Wallingford’s History, 1855-1985. 2005.

A Catamaran Built in Wallingford

By Sarah Martin

Posted March 29, 2025

In early 1960, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer featured the story of Wallingford resident James H. Doyon who was “building a dream”—a 40-foot catamaran—in his back yard. He hoped to have the vessel completed by summer for an eventual voyage to Hawaii.

James lived at 3634 Corliss Avenue N in Lower Wallingford and worked as chief radioman in the U.S. Navy at Sandpoint. His granddaughter, Annie Doyon, has shared with Historic Wallingford several family snapshots of the catamaran (below). Annie tells us her grandmother was not particularly pleased with the enormous catamaran sitting outside her back window and all the noise that came with the construction.

James never made it to Hawaii on the catamaran. He kept it at Shilshole marina and sold it in the early-to-mid-1970s. It is possible the vessel remained at Shilshole for many more years, but the Doyon family doesn’t know its ultimate fate.

Annie shared some additional snapshots below that provide a wonderful glimpse of Lower Wallingford in the 1950s and 1960s. The Ship Canal Bridge, completed in 1962, appears on the eastern horizon in the later snapshot on the right. Thank you, Annie, for sharing your photos!

Sources:

Doyon Family.

Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Jan. 20, 1960.

Wallingford Steps (1800 N. Northlake Way)

By Lynne DeLano & Sarah Martin

Posted February 1, 2025

This story was featured in our 2024 Exploring Wallingford activity.

The Wallingford Steps were constructed in 2002 when the steep hillside that was filled with blackberries was transformed into a short-cut connection for pedestrians from Wallingford Ave. and N. 34th St. to Gas Works Park and the Burke-Gilman Trail.

The steps could also be called Vince’s Steps, after longtime Wallingford resident Vince Lyons, a city planner who lived five blocks north of the “berry barrier.” An architect by trade, he “first conceived the idea in April 1988, jotting a doodle onto a piece of scrap paper that he ha[d] kept for nearly 14 years. He was president of the Wallingford Community Council at the time.” When a developer, Regata, announced plans to redevelop the slope into condominiums, Vince lobbied Regata to incorporate the Wallingford Steps into the plans. With Regata’s investment and a neighborhood matching-fund grant from the City of Seattle, the Wallingford Steps became a reality.

A circular mosaic entitled “Pond” was created and installed on the lower landing by artists Benson Shaw and Clark Weigman. Both artists specialize in public art. The mosaic features over 400 stainless steel cutouts based on children’s drawings and 450,000 hand-set stained glass pieces. Pond represents a “transition from neighborhood terrain to nearby Lake Union. It “reads alternately as ripples or orbs, a huge drop of water, a microscopic image, a mirror sky with constellations, earth/ocean with flora, fauna and fossils.”

The Wallingford Steps also provide a wonderful view of Gas Works Park, Lake Union, and downtown Seattle, along with beautiful art and a short-cut to Lake Union and the Park.

Sources

Seattle Parks and Recreation

“No More Brambles in Visionary’s Path,” The Seattle Times, Jan. 28, 2002.

Linnea Westerlind’s Year of Seattle Parks

Lunde & Stoe Residences – Meridian Ave N

By Linda Sewell

Posted December 17, 2024

This story was featured in our 2024 Exploring Wallingford activity.

Stroll down Meridian Avenue south of N 40th Street to find the quaint brick Tudor Revival homes built by Lunde & Stoe just before the Great Depression.

Norwegian immigrants Ole Lunde and Paul Stoe worked as carpenters for years before forming a building contractor company during Wallingford’s second housing boom of the 1920s. Lunde & Stoe, Inc. was active from 1923 to 1928 and was located for a few years at 1822 N 45th (across from Interlake School) with business hours well into the evening and on Sundays to better compete for real estate customers. They are typical of merchant builders from that period who would purchase several lots on a block, design and build multiple homes simultaneously, and then market the homes directly to the public. Each merchant builder brought their preferred subcontractors on every project. For example, Lunde & Stoe used Colodgero Cagnina, an Italian immigrant, as the sewer contractor for several Wallingford projects.

Many of their building projects were in the Green Lake area, but their most noticeable contribution to Wallingford overlapped with the demise of their partnership. They built a total of eleven brick houses in clusters at corners along Meridian Avenue N. They are almost exclusively Tudor Revival in style. More of their Tudor Revival brick homes can be found near the corner of Burke Avenue N and N 42nd Street

The Tudor Revival style and Tudor Composite subtype can be found throughout Wallingford. Use of the style peaked in the 1920s during Wallingford’s second residential building boom. The style loosely interprets the decorative elements of the Jacobean and Elizabethan buildings of the late Medieval period in England and typically features a dominant cross-gable on the front facade, steeply pitched roofs, decorative half-timbering, tall narrow windows (often grouped), and massive chimneys. Gable details, patterned brickwork, and round or Tudor arches are also hallmarks of the style. The Tudor Composite subtype blends design elements of Tudor Revival with Colonial Revival. These include the use of brick detailing to mimic Palladian window configurations, double front gables, front entrance porticos, and the use of shutters.

Sources:

City of Seattle Historic Resource Survey records

https://web.seattle.gov/DPD/HistoricalSite/QueryResult.aspx?ID=1138223777

https://web.seattle.gov/DPD/HistoricalSite/QueryResult.aspx?ID=-1034184940

https://web.seattle.gov/DPD/HistoricalSite/QueryResult.aspx?ID=-765473919

https://web.seattle.gov/DPD/HistoricalSite/QueryResult.aspx?ID=1896609745

City of Seattle Side Sewer cards # 4988, 4986, 3584

Ore, Janet. The Seattle Bungalow: People and Houses, 1900-1940. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2007. Chapters 3, 4

Polk’s Seattle Directories, 1906-37

U. S. Census, 1920-1940

Seattle Daily Times:

Nov. 28, 1923, p. 17

Sept. 21, 1924, p. 43

Oct. 12, 1924, p. 49

June 25, 1925,

Jan. 12, 1928, p. 31

June 11, 1928, p. 31

Sept. 18, 1928, p. 24

Feb. 3, 1929, p. 24

Seattle Post-Intelligencer:

Oct. 1, 1929, p. 18

Wallingford’s Waterfront Quonset

By Annie Doyon

Posted October 26, 2024

This story was featured in our 2024 Exploring Wallingford activity.

The unique, round-arched building at 1301 North Northlake Way is known as a Quonset Hut. This building type originated in 1941 as America prepared for possible war when U.S. Naval engineers were tasked to design a prefabricated, portable structure easily manufactured, easily shipped to potentially far-off destinations, easily assembled by nearly anyone, and easily adaptable for any range of uses. In just a few short years, by the end of WWII, an estimated 150,000 of these steel-frame units had been manufactured. Though many continued to serve military or other government purposes, the buildings also became surplus and were sold to civilians for a wide range of uses. Quonsets are commonly seen in agricultural settings but can also be found as commercial or even residential buildings.

Likely purchased as military surplus, this Quonset was moved to its Wallingford location between 1950 and 1954 just East of Waterway 22 where Stone Way ends. This part of the neighborhood was still very industrial, and while some marine-related businesses were located nearby, 1950 maps indicate only a wharf at this particular location. Images from 1954 show both this Quonset in place along with an additional Quonset with a 3/4 round roof and one vertical side wall sitting at the wharf’s end. This Quonset, when first installed, had its original, typical design with a large garage door type opening on the front (West) with a pair of windows on each side and no openings or windows along either of the long side walls. Between 1965-1966 the site was being improved, with sewer added at that time along with a mezzanine, store-front windows and a single-person entry door on the front, and a flat-roof overhang was put at the Northwest corner. This addition has been altered over time, but this porch roofline remains. At this time, Emerson G. M. Diesel was leasing this property, which was still owned by King County, having been purchased many years prior with funds from a bond issue for a ferry landing. A 1979 image shows the second Quonset still present along with another gable-roof, frame building also at the end of the wharf. In the 1980s this building housed Wesmar Marine Electronics, and most recently, Lake Deli Mart.

Sources:

King County Assessor, property record cards

Seattle Public Library, Werner Lenggenhager Photograph Collection

Washington Department of History & Archaeology, “Quonset Hut (1941-1960).”

Twin Craftsman Bungalows

By Linda Sewell & Sarah Martin

Posted January 27, 2024

This story was featured in our 2023 Exploring Wallingford activity (point number 11).

These twin Craftsman-style houses at 4025 Wallingford Ave. N and 4030 Densmore Ave. N were developed by Henry Brice, who lived at 4234 Densmore Ave. N. Brice is described as a “street contractor” or “grader” in various editions of Polk’s Seattle Directory; however, he worked regularly as a developer in Wallingford and “hoped to erect a hundred or more homes on his large landholdings in the neighborhood,” (Ore, 53).

Using mass production techniques and uniformity of components, Brice was involved with the construction of many Wallingford residences in the years prior to World War I during Seattle’s first north end building boom. He reportedly “amassed 500,000 feet of lumber recycled from the dismantled 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition” within blocks of this location, “very likely” reusing it in the framing of many Wallingford homes (Ore, 67).

In 1910, Brice partnered with builder Joseph Parker to build speculative houses in Wallingford. They built dwellings in small groups, often in a row along the face of a block. For example, he developed 4015, 4017, 4021, 4025, 4029, and 4033 Wallingford Ave. N as well as 4020, 4022, 4026, and 4030 Densmore Ave. N.

These featured twin Craftsman bungalows reflect Brice’s repetitive use of house plans and materials. Each residence is 1-1/2 stories and features wood-shingle exterior cladding, a cross-gable roof, and a prominent brick and cobblestone chimney that faces the street. Cobblestones are found in Brice’s other properties, including nearby 4015 Wallingford Ave. N.

Sources:

Building Permits, SDCI, City of Seattle.

Ore, Janet. The Seattle Bungalow: People & Houses, 1900-1940. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2007.

Side Sewer Record Cards, City of Seattle

The History of Wallingford Playfield

By Joice Denend and Sarah Martin

Posted July 15, 2023

Wallingford Playfield was dedicated in 1925 during a ceremony organized by the Wallingford Community Club. The event included remarks by Seattle City Council President, Bertha K. Landes, and performances by students from Lincoln High School and St. Benedict’s School. The North Central Outlook, a new neighborhood newspaper published at 4203 Woodlawn Ave. N, reported that 2,500 people attended the opening day festivities.

The playfield occupied one city block, between Wallingford Ave. N, Densmore Ave. N, N 42nd St., and N 43rd St. It hosted school and club sporting events and activities and provided Wallingford a community gathering space.

Talk of expanding the park began in the 1950s, but a proposal calling for the condemnation of two blocks of houses was met with vocal resistance and the effort stalled. Among the ideas that the City considered were to take the block south of today’s park along Wallingford Avenue, between 41st and 42nd streets, and to build a fieldhouse and indoor swimming pool for the public and school to use.

In the late 1960s, using Forward Thrust Bond Issue funds, which supported the largest expansion of the park system in Seattle history, the City improved the existing playfield and acquired the block to the west between Densmore Ave. N and Woodlawn Ave. N. It demolished 16 houses and a church and eliminated a block of Densmore Ave. N in 1969-70 to expand the playfield. Improvements to the playfield included adding tennis courts, a wading pool, a shelter house, and athletic fields.

The playfield was renovated in 2019 to ensure current safety and accessibility standards. The park’s short, steep west border is a native plant garden. Today, the playfield is one of 20 city parks to have a wading pool.

Sources:

Preliminary research by Patrick Long.

Seattle Times, May 16, 1925; Nov. 28, 1951; June 4, 1952; Oct. 10, 1967; Oct. 11, 1968.

North Central Outlook, May 21, 1925.

Seattle Municipal Archives Photographs.

History Link: Forward Thrust Bond Issue

The Rubber Tree: Wallingford’s One-of-a-Kind Contraceptives Shop

By Sarah Martin

Posted July 24, 2022

With the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent decision reversing Roe vs. Wade, we thought it timely to recall that one of the nation’s first over-the-counter contraceptive shops operated right here in Wallingford.

In 1975, a contraceptive specialty shop known as The Rubber Tree opened at 4426 Burke Avenue N in Wallingford. This one-of-a-kind boutique opened as a project of the Seattle Chapter of Zero Population Growth (ZPG), a political movement that emerged in the late 1960s that advocated for demographic balance that results in a population that is neither growing nor declining.

The shop specialized in non-prescription contraceptives, bringing the “sale of birth control devices out from behind drug store counters and away from tavern restrooms,” (Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 7/15/1975). They also sold books on population growth, colorful environment-themed posters, and political bumper stickers and t-shirts, and distributed free health literature.

The unassuming shop quickly garnered nationwide attention, from public health researchers to college campus newsrooms. One report suggested the shop, “situated on a quiet residential street,” served an estimated 7,000 customers in 1977. It said, “in addition to making contraceptives easily available and working to abolish social taboos, the Rubber Tree’s mission includes the dissemination of medically accurate information in the hope of reducing the incidence of venereal disease and unplanned pregnancies,” (The Family Planner, 1978; The Michigan Daily, 1976 ).

Another account of the shop said: “The laid back staff and volunteers tackle sexuality with a balance of humor and seriousness, yet are trained to answer questions about contraceptives without attempting to take the place of professionally trained family planning counselors. The staff refers some customers to more than twenty-five local clinics and services. Selling 1500 condoms per week in the store and through its mail order catalog, the Rubber Tree is clearly meeting an important, yet overlooked need,” (Rubinstein, 1994).

The storefront shop remained a fixture of Wallingford for a quarter century and continued online sales until 2010. Vanishing Seattle featured the shop on Facebook in 2016. The building (pictured below) is proposed to be demolished.

Sources:

No author. “A Tree Grows in Seattle.” The Family Planner. Vol. 9, 4-5 (1978): 3-5.

No author. “Ballooning Sales.” The Michigan Daily. Jan. 10, 1976.

Perkins, Carol. “Not Your Usual Boutique.” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, July 15, 1975.

Rubinstein, M. “Condom Sense.” ZPG Reporter. Vol. 26, 4 (1994): 6.

Public Art in Wallingford: Animal Storm

By Mike Ruby

Posted December 5, 2020

Wallingford is rich in public art, from the statue of Good Dog Carl in the Meridian Playfield children’s play area by Kevin Pettelle to the Sundial at the top of Kite Hill in Gas Works Park by Charles Greening and Kim Lizare. One of the more visible pieces of outdoor public art is the Animal Storm statue at the corner of N 45th St. and Wallingford Ave. N (shown below in an older photo by Paul Dorpat).

Animal Storm was commissioned for the 1984 conversion of the old Interlake Elementary School building to stores and apartments as the Wallingford Center. This “adaptive reuse” of an historic building is just one of several examples how historic preservation contributes to the strong historical vibe that runs through Wallingford.

In 1984 a competition was held to select a prominent feature to mark the corner that, for many, is the epicenter of Wallingford. Three finalists were selected to create mockups of their proposals, which were then exhibited in the Williamsburg Savings Bank (later Metropolitan Savings and Loan) lobby, where the Chase Bank branch is now located. Neighbors were invited to visit the display and vote for their favorite. The overwhelming winner was Animal Storm by Wallingford resident, Ron Petty. In addition to the attractive physical model it was described as depicting animals found in and around Wallingford.

Ron Petty has done several other public art statues around Seattle. He designed the large Seattle Fisherman’s Memorial statue and granite walls, located at Fisherman’s Terminal, commemorating workers who lost their lives in the commercial fishing industry. His Salmon Dance, granite columns topped by three ascending salmon, is at One Union Square, downtown.

In July of 1985, the statue was unveiled with, indeed, more than 60 animals from almost 30 species pictured in bas-relief on the 18 foot tall pillar. If you step behind the bench that wraps around the back of the site you will find a small plaque that lists many, but not all, of the animals represented on the pillar. There are at least 13 different birds, 7 fish, 7 mammals and a garter snake. A useful way to introduce children to the statue is to ask them to find the particular animal listed as you call them out. Admittedly, it will be hard for most to tell the difference between a bass and a perch, but that is half the fun.

Unemployed Citizens League

By Kim England

Posted August 8, 2020

In our ongoing electronic wanderings though various archives we’ve found another Wallingford gem. In the early 1930s, on North 37th Street, just east of Wallingford Avenue (where the Wallingford Bible Fellowship is today), stood the Wallingford branch of the Unemployed Citizens League (UCL). Meetings were held on Fridays at 8 p.m. Click here to see a photo of the building from the UW’s digital collections.

Our friend, Paul Dorpat, talked about the UCL in his July 5, 2014 edition of Seattle Now and Then – it focused on the New Deal. (The photo at the left appeared in his piece.)

These photos resonated with us because of the current moment of increased unemployment and social action associated with Black Lives. The UCL was founded in West Seattle in July 1931 and quickly became an important political force in Seattle. The unemployment rate hovered around 25 percent, and the lack of a social safety net (this was pre-New Deal) prompted the rise of this mutual aid co-operative – there were about 20 local UCLs around Seattle, including the one in Wallingford. This mutual aid movement included borrowing land to plant and harvest food, which along with firewood and clothing was distributed through their commissaries. The UCL fought for economic and social justice, provided assistance programs for unemployed workers, and organized residents to press the government for more jobs and unemployment relief assistance.

Interested in learning more? See these resources available at the Seattle Municipal Archives.

Wallingford Victory Garden

By Kim England

Posted June 10, 2020

In the early spring, we noticed a surge of online groups and news stories highlighting one local response to COVID-19: growing your own food in the yard. What particularly drew our attention was that they are often framed as the comeback of Victory Gardens, or how to start “a coronavirus victory garden.” Why? One thing our occasional archive ‘scouring’ turned up a while ago was a Seattle Post-Intelligencer photograph titled “Victory Garden in Wallingford, August 1944,” (in the MOHAI photograph collection at UW).

During the Second World War the US Department Agriculture published guides to create and maintain Victory Gardens. The poster on the left is one of many that the USDA published, and can be seen at the start of a restored version of the 1942 USDA’s film on creating a Victory Garden.

The Wallingford photo shows several people working in a large lot filled with rows of produce, and the caption notes that, “The Victory Gardens provided a place for neighbors to get together and raise their own food.”

The photo caption also suggests the photo was taken in the 2300 block of Corliss Avenue. That didn’t seem to be the right location (at least today there isn’t a 2300 block). So, on a recent socially distanced, mask-wearing walk we used the photo to figure out it is the 3700 block, at the intersection of Corliss Avenue N and N 38th Street. But wait, there are some older houses (c. 1920s?) where the Victory Garden must have been?! Turns out, in another intriguing twist, those houses were moved there from out of the path of where I-5 was to be built!

Do you know of other Wallingford homes that were moved for similar reasons? Do you have a Victory Garden story to share? Do let us know: info@historicwallingford.org.

The Genealogy of a Wallingford House

By Chuck Timpe

Posted March 3, 2020

After purchasing our Wallingford Craftsman bungalow home at 1604 N. 35th Street in 2012, my wife and I have been curious about the history of our house and its prior owners since its construction in 1924-25. We recently visited the Washington State Archives at Bellevue College, where property tax records are kept dating back to the late 1800s. I also visited the King County Archives where deeds and mortgage records are stored and available to the public. Using these records, together with annual Seattle Polk directories, US Census reports and some genealogy research sites, we were able to piece together some interesting facts about the history and occupants of our house, as well as a few of our neighbors’ homes. Our house and three other adjacent houses sit on two lots that were part of 1883 Corliss P. Stone’s “Lake Union Addition to the City of Seattle” plat, which today comprises a large section of Wallingford, stretching from 45th Street to Gas Works Park on the north shore of Lake Union.

According to the 1920 tax rolls, our two lots were owned by Martin Buerk, who had purchased the two lots in 1889 for $375 from Nellie Andrews. Nellie was the daughter of Seattle pioneer Hiram Burnett and one of the original seven land owners of the C.P. Stone plat. Buerk sold the lots to Leslie Root in 1924. Leslie Root and his brother Edgar had started a real estate company in Wallingford in 1923. The Root Brothers subdivided the original two lots into four parcels, on which they built four Craftsman-style bungalow houses in 1924 and 1925, which still stand today on N 35th St. and Woodlawn Ave. These four houses were the typical one-story, 1200 sq. ft. bungalows, all built with the same (or reverse) floor plans.

Originally from Pennsylvania, Leslie Root had been a teacher for King County in Newcastle, and his older brother Edgar was a contractor before they both worked as real estate agents for Park Junction Realty in Wallingford in 1920. Three years later they opened the Root Brothers real estate office on 45th Street and Stone Way (where Archie McPhee’s now stands), advertising themselves as “Realtors Specializing in North End Homes; We Build to Suit.” Leslie, a life-long bachelor, lived with his brother Edgar’s family in the Wallingford area, first on Woodland Park Ave., Midvale Ave., then later on W Green Lake Way.

Early Occupants

Our house was first purchased by A. Y. and Mary Drain in August 1924 under a sales contract to be paid in monthly installments. A. Y. Drain was a department manager for MacDougall & Southwick Co. in downtown Seattle.

A.Y. Drain was born in Texas in 1889, then moved with his family to Bellingham where his father was a farmer in 1900. A.Y. was a shoe salesman in Bellingham before moving to Seattle. He later opened and managed the Jacqueline Slipper Shop on 3rd and Pike in 1931.

Although the Drains occupied our house through 1926, they apparently never took title, for Leslie Root sold the house in 1925 to David and Emily Carlson “subject to the Drain sales contract.” It seems that the Carlsons never occupied the house, as David Carlson died later that year in 1925, and Emily continued to live at another address in Seattle during the years they owned the house. In 1927 A. Y. Drain quitclaimed his deed to Emily Carlson, and in 1928 Emily Carlson sold the house to Aniceto Tiberio, who lived in our house for the next 37 years.

Aniceto Tiberio immigrated to America from Italy in 1909 at the age of 28, and by 1911 was living in Wallingford at N 34th St. and Wallingford Ave., where he worked at nearby Seattle City Lighting at today’s Gas Works Park. In 1915 he married Caroline, also an Italian immigrant. The family lived at other Wallingford addresses prior to 1928, including at the corner of N 34th St. and Meridian Ave. near Gas Works Park. They had three children by the time they purchased our house in 1928, moving into the small 2-bedroom Craftsman bungalow with three young children.

It is unclear how long Aniceto worked at Seattle City Lighting, but by 1929 his occupation was listed as a blacksmith for Northern Pacific Railway. From 1930 through 1957 he continued to work for the railroad at King Street Station.

Aniceto and his wife raised their family and lived out the rest of their lives in our house. Their oldest son Armand began working as a mechanic for Boeing, where he retired after 45 years. The younger son Paul also started working at Boeing, in 1943. In 1948 he was a division manager at Sears Roebuck, but returned to Boeing by 1951, where he continued to work at least through 1974. Their daughter Rose began working as a saleswoman in 1937 at the S H Kress &Co. “five and dime” department store in downtown Seattle.

Caroline Tiberio passed away in 1960, after which their youngest son Paul and his wife Eva moved back into the house with Paul’s father. Aniceto died in 1965 at the age of 74, and Paul and Eva continued to occupy the house for another year after his father’s death. The Tiberios have many descendants and a large extended family that still live in the Seattle area today.

Later Occupants

After the Tiberios sold the house in 1966, there were numerous subsequent owners and renters over the years. Occupations included a waiter at the Roosevelt Hotel in 1967, who later became (and currently is) a State Farm Insurance agent; a warehouseman; a comptroller at Lincoln Moving and Storage; an employee at the School for the Blind; and a railroad worker.

Other Early Occupants in our Neighborhood

Like many of the homes in South Wallingford in the 1920s to the 1950s, our three neighbors’ look-alike Craftsman bungalow homes, all built in 1924-25, were occupied by mostly blue-collar workers. We found their early owners’ occupations included a bridge watchman, a carpenter/cabinetmaker, a barber, a railroad conductor, a railroad signalman, a local meat market manager, a shipping clerk for an importer/exporter, an engineer, a pressman for a printer, a laundryman and a foreman at Union Oil Company.

Historic Wallingford thanks Chuck for this wonderful contribution.

Re-discovered Photo Shows Early Wallingford Business

Posted January 29, 2020

We were excited to receive this old photograph of John’s Shoe Shop from Ron Edge. He recently found it on eBay and had never seen it before. It was unfamiliar to us, too.

The photo didn’t have any identifying information beyond what appears in the image. Luckily, it has important clues that allowed us to piece together a story. Thankfully, the unknown photographer captured the street signs in the top right corner – N 45th and Meridian Ave. – placing it in Wallingford. With this information, we turned to Seattle city directories to see if we could find any trace of John’s Shoe Shop.

Beginning randomly with the 1920 directory, we turned to the Shoemakers and Repairers section of the business directory, where dozens of businesses were listed. It didn’t take long to determine that John must have been John H. Keim, who managed a shoe shop at the northeast corner of N. 45th Street and Meridian Avenue from 1916 to 1921. Also during this time, Keim briefly lived around the corner at 4424 Bagley Avenue.

Ron’s photo must have been taken during these years, 1916 to 1921, and it probably shows John Keim himself standing in the doorway.

Public records reveal Keim was born in 1878 in Minnesota, apparently never married, and lived in Seattle at the time of his death in 1949. Ron’s search of The Seattle Times suggests Keim was in the shoe business for many years, as early as 1904. Here are a few clippings:

The directories also suggest Keim wasn’t the only person to operate a shoe business at that corner. James A. Irvin came before him and Adam E. Cooper followed him. Within a few years, there was a more substantial building at this busy intersection. Today, CVS occupies this corner.

Many thanks to Ron for sharing this photograph and these newspaper clippings with us!

1939 & 1952 Cookbooks by Wallingford Women

Posted November 23, 2019

As you use this book you’ll find

A host of recipes, the best of their kind.

You’ll use them and love them and keep them about,

For the best cooks in Wallingford have tested them out.

OES Wallingford Chapter cookbook, 1952

We recently heard from JoAnne, who prefers we use only her first name, about an interesting piece of Wallingford history. She shared with us two cookbooks produced in 1939 and 1952 by the Order of the Eastern Star (OES) Wallingford Chapter No. 204. She has no connection to Wallingford and is not a member of the OES, so she was unable to provide any historical context about the cookbooks. She believes the cookbooks came to her by way of a used bookshop or something similar. We are grateful to Joanne for sending digitized copies for us to share.

The cookbooks (see the links below) provide wonderful snapshots of Wallingford’s club women in the mid-20th century. They include recipes for everything from Norwegian Meatballs to Yum Yum Salad and feature the names of dozens of recipe contributors, who are nearly all women.

1939 Cookbook

1952 Cookbook

1952 Index of Names

Are there any OES members among our readers? Does anyone recognize names from the cookbooks? If so, send us your story to info@historicwallingford.org!

Relocated Bassett House has Colorful History

Posted October 13, 2019

At a recent Historic Wallingford event, historian and designer Thomas Veith discussed the residential architecture of our neighborhood, showing dozens of images to illustrate building trends and fashions.

One person in the audience, Lee Bassett, noticed his house, 1603 N. 48th Street, among the many photographs. Tom said that Seattle architects Folke Nyberg and Victor Steinbrueck had identified the house as “significant to the Wallingford community” in the mid-1970s when they surveyed Wallingford for surviving historic architecture. Long intrigued by the old house, Tom called it an “interesting mishmash of styles,” suggesting it has changed over time.

We were delighted when Lee agreed to share old photos and stories of the house, which coupled with additional research, reveal clues about the building’s evolution and a rather colorful story.

Early History

The house was built in 1901 on a large corner lot at 46th and Stone Way, where Bizzarro Italian Café and Blue Star Pub & Café now stand. Its address was 1307 N. 46th, according to some sources, and 4512 Stone Way according to others.

The home’s early history is connected to some interesting Seattle characters. One connection came to light when, during a home renovation, Lee found an old postcard from 1908 that was addressed to [George] Elwood Hunt, whose family lived at 1307 N. 46th (see image below). At the time, Elwood was about 17 years old and a student at Broadway High School who would soon enter the University of Washington. His parents were George W. and Mary Emma (Carkeek) Hunt. Elwood used this Wallingford address as late as 1916 when his son, George E. Hunt, Jr., was born (see image). By 1920, the young family lived at 5315 Latona Avenue before relocating to Puyallup. If you recognize George, Jr.’s name it’s because he was one of the “Boys in the Boat” – a rower on the UW’s 1936 Olympic rowing team that took gold.

Another interesting connection to this house comes a few years later – in the 1920s – with owner Joe (Giuseppe) Mangini, who emigrated from Italy in about 1902. Joe was well-known in 1920s Seattle. He and his brother Jack (Giacomo) Mangini were principals in the Seattle Garbage Co., sometimes called Seattle Hauling Co. or Seattle Garbage and Hauling Co., which contracted with the City of Seattle for many years. In 1925, Joe applied for a city permit to excavate a basement at 1603 N. 48th Street, where he would later move the house. Lee recently spoke with Joe’s great-grandnephew, John Mangini, who confirmed our hunch that Joe moved the house to clear the lot at 46th and Stone Way and redevelop it with a more lucrative mixed-use commercial and residential building – today’s Blue Star building. Joe and his wife Mary then resided in the new building.

The ownership of the house in the late 1920s and 1930s has not been researched. Lawrence Westerman purchased the house in 1942, at which point Lee thinks the structure had changed little from when it was moved. One possible exception is the basement. Physical and documentary evidence suggest the house did not sit on a similar basement at its original location. For instance, the extant header for the back door, which is no longer used, suggests that the door would have opened directly over a staircase leading to the basement. The pre-move 1919 Sanborn map (see image below) supports this hunch about the basement. It shows a porch wrapping around the north, west, and south sides of the house, but part of the west porch was removed when the house was moved to accommodate a stairwell to the basement. The post-move 1950 Sanborn map (see image below) illustrates this and the addition of a garage, presumably added when the house was moved, that opened into the basement.

Since 1950

Lee said the house functioned as a rental from the mid-1960s until he and his wife Carol purchased it in 1974. A 1965 photo shows the house prior to changes made for its use as a rental, which included windows, wiring, interior walls, and plumbing. The result was a significant departure from its appearance of the previous 40 years.

When they purchased the house, Lee and Carol were aware that it had once looked different and wanted to return it to an appearance that they imagined it once have had. They were without the benefit of historic photographs to guide their work. The two most striking exterior features that seemed out of place were the porch with its altered gable roof and the replacement aluminum windows. They pieced together what they believed would have been the shape of the wrap-around porch, and, as the demolition progressed, they found physical evidence to guide their decisions. Lee built the wood sash windows and front door that replaced the aluminum windows and solid core door installed a decade earlier. Other projects followed on the interior with an eye toward restoring the home’s turn-of-the-century character.

The Bassetts have owned the house for 45 years, but Lee sees it with fresh eyes: “I’ve been thinking about how the house would have been supported in its move and how that support would be extricated once the move had been completed. It turns out that there are cutouts in the foundation which I had formerly just thought of as windows and ventilation. These cutouts are on the north and south sides and correspond to each other in a way that girders could span the house while being transported. It was kind of fun to have that light bulb come on for me!”

We’ve searched and searched for a photo of the house in-transit to its current lot at 48th and Woodlawn with no luck. We and the Bassetts are hoping one turns up!

Sources

Bassett, Lee and Carol. Personal photograph collection.

City of Seattle. Building Permit for 1603 N. 48th Street. May 1, 1925.

Sanborn Company Fire Insurance Maps, 1919 and 1950. Seattle Public Library digital portal.

The Seattle Times. Seattle Public Library digital portal.

Street Renaming in Wallingford, Fremont & U District

Posted September 15, 2019

If you’ve done any historical research on Wallingford-related topics, you’re well aware that the street names have changed over time. Wallyhood and various local history blogs recently shared an interesting piece by Rob Ketcherside about street names in Fremont, Wallingford, and the U-district. Here it is again – it’s a great read!

Willis & Alice Batcheller House – 1848 N 51st Street

Posted June 15, 2019

We were delighted to hear from Janis Levine about her house at 1848 N. 51st Street, situated mid-block between Meridian and Wallingford avenues. She shared with us a few photos, which led us to discovering her house in one of builder Jud Yoho’s house catalogs. A brief synopsis of the house and its original owner follows:

Newlyweds Willis T. and Alice Batcheller were the first owners of the bungalow at 1848 N. 51st Street. They purchased it for $1,600 in 1914 from Yoho’s Craftsman Bungalow Co. Prior to the purchase, in 1912, Margureite Hieber, a widow who inherited five consecutive lots (including Levine’s), sold the lots to Jud Yoho’s company for development. The company subsequently built this modest “attractive bungalow” that it advertised as plan number 325 in its 1913 catalog, pictured below. (We haven’t yet studied the adjacent lots.)

The original floor plan, also pictured below, exhibits a typical small Craftsman bungalow plan. Its long, narrow arrangement with private bedroom spaces clustered on the left and the interconnected common-space living and dining rooms and kitchen at right is a typical plan that Yoho advertised as utilizing “every available bit of space.”

Levine purchased the house in 1989 from the Batchellers niece, who gave her old photographs of the home and information about the longtime owners. Willis T. Batcheller (1889-1975) was a consulting engineer who specialized in electric and hydraulic projects. He earned a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering in 1911 and a master’s degree in 1915 – both from the University of Washington. During his career, he was associated with some of the largest and most important electrical power projects in the Northwest.

- He worked for Seattle Light and Power System from 1912 to 1921, including designing turbines at the Lake Union steam-electric plant and planning for the Skagit River power project.

- He then produced the original survey and report on the Columbia Basin Reclamation Project for the State of Washington and prepared the original designs for the Grand Coulee dam and power house.

- He served as chief engineer for the Quincy Valley Irrigation District for 14 years.

- He was president and chief engineer of the Canadian-Alaska Railway company that proposed building a railway from Seattle to Vancouver, BC, to Fairbanks, Alaska.

The Batchellers lived in the house at 1848 N. 51st Street their entire lives together.

We thank Janis Levine for sharing the story of her house!

Further Reading:

Batcheller, Willis Tryon, Papers. University of Washington Special Collections. Accession No. 247-001. Overview of the collection: http://archiveswest.orbiscascade.org/ark:/80444/xv25833

Yoho, Jud. Craftsman Bungalows, 1913 Edition. Seattle, WA: Craftsman Bungalow Co., 1913. [The house at 1848 N. 51st Street is plan no. 325, featured on pages 56-57.]

Swanson’s Shoe Repair a Fixture of Wallingford

Posted May 18, 2019

Many thanks to the Swanson family for sharing their old photos with Historic Wallingford. We’ve included several in the gallery below.

Swanson’s Shoe Repair, 2305 N. 45th Street, traces its roots to 1928 when Swedish immigrant George Swanson, Sr., opened Progressive Shoe Renewing at 612 Union Street in downtown Seattle. The business moved to Wallingford in 1946 where the Swansons — George, his wife Hannah and their two sons George Jr. and Raymond — lived. George Sr. and his sons were active in the Wallingford Boys Club and its soccer team (pictured below). George Jr. took over the business when his father retired in 1959, and he ran the business until his retirement in 1990. Today, Swanson’s Shoe Repair is run by George Jr.’s son Daniel and daughter Patty and is one of only a few shoe repair businesses in Seattle.

Click on the icons below to see full images.

Further Reading

Dorpat, Paul. “The Shoes Fit.” The Seattle Times / Pacific NW Magazine. November 4, 2007.

Leach-Kemon, Erin. “Siblings Team Up to Help Family Business Hit 100-Year Mark.” Wallyhood. March 2, 2010.

Wallingford and Jud Yoho’s Bungalow Magazine

Posted April 21, 2019

The Seattle Public Library has a near-complete run of Bungalow Magazine, which was published in Seattle between 1912 and 1918. The publication’s founder and early editor was Jud Yoho, an all-in-one real estate broker, designer, and contractor, who was known in Seattle for his bungalows. To promote his business, Yoho built and moved his family into a showhouse in Seattle’s Wallingford neighborhood in 1911 (pictured at right). He featured this and a handful of other Wallingford bungalows in his magazine. Most of the homes are still standing, and they are described below.

Yoho showcased his own house at 4718 2nd Avenue NE in the July 1913 issue (p. 7-12) “because of the favorable comment it had elicited from everybody who has seen it.” He described the house as “neat and distinctive,” with “an air about it which makes it stand out among its neighbors as just a little more artistic and cozy looking.” The house could be built for just $2,900, and Yoho included in the magazine several pages of building specifications.

The magazine featured several houses along Wallingford Avenue. The April 1915 issue (p. 210-20) included the residence of Minta Lulu Smith at 4334 Wallingford Avenue N (pictured below). Architect Stephen Berg designed the house, and Smith purchased it in 1914 for $4,250 through the real estate firm Metcalf & Metcalf. In his colorful write-up, Berg called Smith’s house “one of the most attractive local productions.” He highlighted its “simplicity of design, the happy arrangement of the rooms and the splendid provision made in modern conveniences to guarantee a comfortable and workable home.” And, he called out one striking feature on the home’s north side: the rustic brick chimney that rises through the roof to a height of fifteen feet.

(4334 Wallingford Avenue N, shown in 2019 and 1915)

The same April 1915 issue featured another Wallingford house, this one at 4115 Wallingford Avenue N (pictured below). Built by Jud Yoho’s Craftsman Bungalow Company for just under $3,000, it was home to Lulu E. Thomas. In describing the house, Yoho noted the distinctive “semi-octagonal bay window” behind which is a “roomy” living room with a “cheerful” fireplace. He summarized it as “an exceptionally serviceable and satisfactory house.”

(4115 Wallingford Avenue N, in 1915 and 2019)

The June 1915 issue (p. 346-53) featured a row of three houses in the 3700 block of Wallingford Avenue N that were designed by architect William Barr and built by the Puget Sound Building Company. The houses were advertised as “good examples of the versatility possible in designing moderate priced bungalows.” Each house design “has an individuality, which stamps it as distinctly different from the other two,” but in “perfect harmony with each other.”

(3701, 3705, and 3709 Wallingford Avenue N, shown in 2019 and 2015)

Bungalow Magazine offers a fascinating window into the frenzy and competition of home building in early twentieth-century Wallingford. Many architects, builders, and real estate firms were busy in Wallingford, including architects Ellsworth Storey, Edward L. Merritt, and Charles Haynes, and builders William J. Henry, P. E. Wentworth, and Charles Arnsberg, to name a few. This brief summary only scratches the surface of Wallingford’s rich architectural story.

Further Reading

Doherty, Erin M. Jud Yoho and the Craftsman Bungalow Company: Assessing the Value of the Common House. Master’s thesis; University of Washington, 1997.

Houser, Michael. “Edward L. Merritt.” Washington Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation, 2018. [A biography of Jud Yoho’s business partner.]

Ore, Janet. “Jud Yoho, ‘The Bungalow Craftsman,’ and the Development of Seattle Suburbs.” Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture 6 (1997): 231-43.

Ore, Janet. The Seattle Bungalow: People and Houses, 1900-1940. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2007.

Interlake Public School & Wallingford Center

Posted April 12, 2019

The Interlake Public School is located in the heart of Seattle’s Wallingford neighborhood. It served as a public elementary school for nearly 70 years and is one of the neighborhood’s oldest remaining buildings. Designed by architect James Stephen, the wood-frame building closely follows his “Model School Plan,” a flexible and economical method of constructing schools that allowed for phased expansion. This Neoclassical-style building was constructed in two phases, in 1904 and 1908, resulting in a I-shaped plan. The style is evident in the one-story portico, the Ionic columns, dentils, and the central keystone arch supported by pilasters.

The building served as an elementary school until 1971 and then as an annex to nearby Lincoln High School until 1975. It was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1983 and was developed into shops and apartments, today known as Wallingford Center.

Further Reading

Krafft, Katheryn H. Interlake Public School National Register of Historic Places nomination form, 1983. Source: Washington Department of Archaeology & Historic Preservation, WISAARD.

Ochsner, Jeffrey K. (editor). Shaping Seattle Architecture: A Historical Guide to the Architects. Second ed. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2014.

Thompson, Nile, and Carolyn J. Marr. “Interlake.” Building for Learning: Seattle Public School Histories, 1862-2000. Seattle, WA: Seattle Public Schools, 2002.